The Very Early History of Dublin

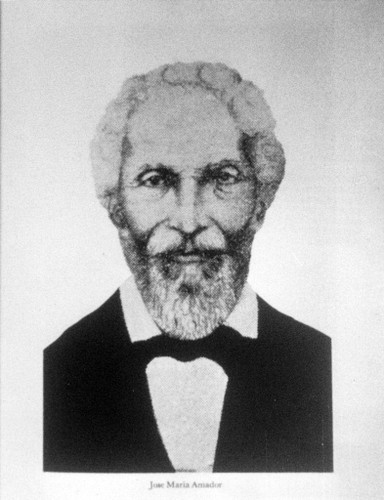

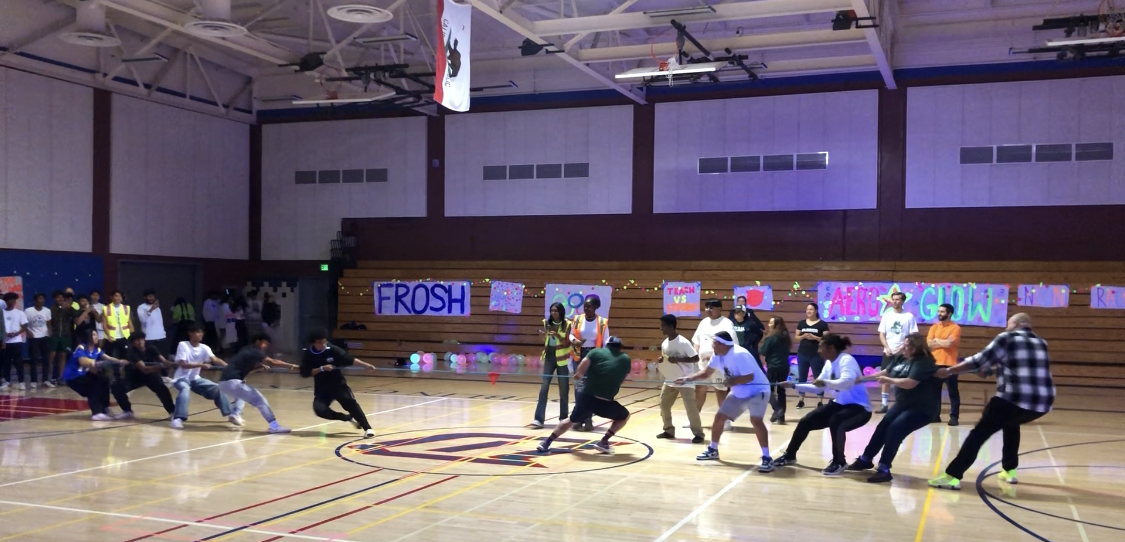

A drawing of Jose Maria Amador, when he was in his old age. (Source: Online Archive of California, and City of Dublin Heritage Center)

When we gaze upon the seemingly endless suburban expanse of Dublin, we think not of the days of pioneers, agriculture, and hardship but instead that of neighborhoods, traffic, and leisure. Indeed, it is hard to think that our big city was once a small town at the crossroads of two ancient trails. But, with enough imagination, we can take ourselves back to the time when a lake sat in the middle of the Amador valley, and the thought of a city where Dublin sits now, was a fever dream.

The First People

Before there was a town, there was nothing but freshwater marshes and fields of golden grass. The first people to live here were the Ohlone Native Americans. In Dublin, the Chochenyo speaking Ohlones were the most common, but there were instances of Bay Miwok Native Americans arriving into the area.

Like today, the region was very diverse. Around the Alamilla Springs (which once bubbled at the corner of Dublin Blvd and Dougherty Rd) were three main tribes. The Seunens, the Pelnans, and the Yrgins. Sources estimate that 200 to 400 Native Americans lived in one of these tribes.

The area was plentiful in resources for all. With various creeks and arroyos all flowing into a large lake that sat at the valley’s center, there was plenty of game and plants for the harvesting. In addition, they sat at a prime spot for trading, as they were on a central walking route between the Suisian and San Francisco Bays.

Spaniard Conquest

On April 1st, 1772, sixteen men made their way through Dublin, led by Pedro Fages, a lieutenant. They were returning from a failed expedition to find a land route to Drakes Bay. Little did they know, their exploration of the new valley would have dire consequences for the people who lived there.

Father Juan Capresi, who was on the expedition in search for a new mission site, wrote down detailed information in his journal. A section of his journal pertaining to the exploration of the Dublin region is listed below:

“We set out at six, following the same valley in a southerly direction, the excellence of the road continuing with many trees… It is a very suitable place for a good mission, having good lands, much water, firewood, and many people.”

In Capresi’s journal, he reports that they stopped at a water hole on April 2nd. That water hole was the Alamilla Spring.

In 1797, Mission San Jose would be constructed on the other side of the hills, but already by then there had been felt the ill effects of Spanish rule of the new Alta California on the aboriginal people, in the matters of disease, starvation, invasive species, and more.

Eventually, the new missionaries at Mission San Jose would begin to convert the Native Americans to Roman Catholicism. They would entice the Native Americans to join, but once they were baptized, they could no longer leave the mission. They forfeited all vestiges of their formal life and culture. In addition to this, a constant state of poor sanitation, overcrowding, and disease led to a miserable experience. Punishments like beatings and floggings would be administered to those who misbehaved.

There was some sort of relief to this, as in 1836 Mission San Jose closed (as a government-funded religious establishment), and its population was freed. To divide up the vast lands of the former mission, it was sold to the landowners of the region. It was here that a former major-domo of Mission San Jose was given approximately four square leagues of land. This man was the founding father of Dublin, Jose Maria Amador.

Jose Maria Amador & Rancho San Ramon

Jose Maria Amador was born in 1794 to Pedro and Maria Amador in San Francisco. As a young child, he had been taught to read and write, and just like his father he would become a soldier and fight Native Americans who attacked new settlers. After his fighting career had ended, he would become the Major-Domo of Mission San Jose in 1827.

“He proved to be a very able administrator. He had mellowed by this time and managed the Indians there very humanely… Mission San Jose prospered under his care.” wrote Virginia Smith Bennett, in the book Dublin Reflections And Bits Of Valley History.

His time as Major-Domo would eventually come to a close. Not wanting to let go of such a skilled administrator without compensation, the Mission system granted him approximately four square leagues (or 16,517 acres) of land in the San Ramon Valley and lower Pleasanton area on August 17, 1835. This would be called Rancho San Ramon.

Amador was already well accustomed to this area, as he already lived there since around 1826 to raise cattle. By the time Rancho San Ramon was established, he had a manufacturing shop for soap, leather, furniture, and other commodities.

His original house was adjacent to the Alamilla Spring, at Dublin Blvd and Dougherty Rd. However, his property did not include the Spring itself, so he received an extra 562 acres of land to accommodate that and other such features of the valley. It should be mentioned that Jose Maria Amador’s dwelling (with his wife Dolores Pacheco) was unique, for it was a rare instance of a two-story adobe home.

“The rancho included as many as 400 horses, 14,000 sheep, pigs, thousands of cattle, a vineyard of 1,500 vines, an orchard of 50 trees, and 150 employees.” Wrote Steven Minniear, in the book Dublin California, A Brief History.

Jose Maria Amador would live to see Dublin grow from a simple mission-era ranch to an agricultural town at the midst of the crossroads. His legacy lives on, through most notably the Livermore-Amador Valley, and Amador Valley High School. In memory of him, a portrait of him is now adorned on the wall at the local history section of the Alameda County Library in Dublin

Your donation will support the student journalists of Dublin High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Alex Dion is a junior at Dublin High School. As a passionate advocate for public transit, he primarily publishes articles on transit news and advoacy,...

![[Book Review] Weapons of Math Destruction: The insidious danger of Big Data](https://thedublinshield.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/wmdsarticle-727x1200.jpg)