Op-Ed: Education is Broken, and Only We Can Fix It

“There is no such thing as neutral education. Education either functions as an instrument to bring about conformity or freedom.” – Pedagogy of the Oppressed

What is the purpose of education?

Every student asks this at some point, and we always get the same tired old answers. To prepare us for the future. To make us good citizens and productive members of the workforce.

But frankly, we can do much better than that. And there is no time like now to revisit the question, since public education has become such a point of contention in the ongoing culture war.

Why is this gaggle of governors, legislators and other functionaries so intent on seizing control over education, by banning books and rewriting curricula? Certainly a great deal of it is an opportunistic grab for votes, but there is something deeper to this struggle.

Simply put, the politicians understand something that we, the students of America, do not: education is how society reproduces. In their view, education is a machine, whose purpose is to indoctrinate an entire generation with the appropriate values and attitudes. It is no surprise, then, that they want to control that machine; whoever pulls the levers gets to remake America in their own image.

So, we have one answer to our question: education is a form of social control.

This problem cannot just be chalked up to a few reactionary politicians, though – if we look around our own schools, we can find these mechanisms of control everywhere. The most obvious examples are the security cameras that adorn our halls or the spyware on our computers, but it can exist more subtly – in the format of our classes, and in even the curriculum from which we learn.

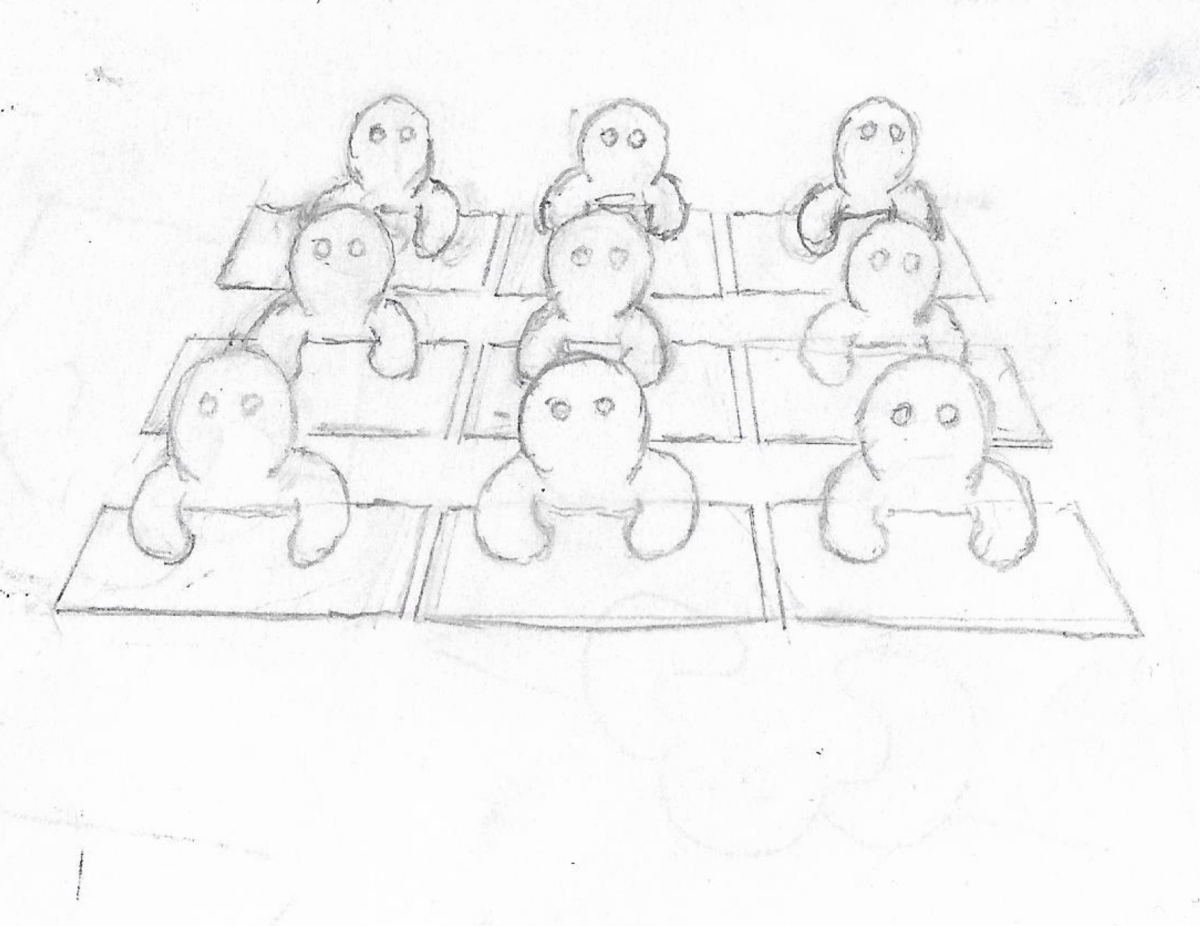

Consider this: as students, we are made to sit in classrooms for eight hours a day, five days a week, as we listen to lectures and take tests and fill out worksheets. It is often an unpleasant experience, but we are told that these are the unavoidable pains of learning.

And what goes into our heads these forty-odd hours? More often than not, it is a collection of “facts,” to be regurgitated on the next test. These facts can be anything – events from history, laws of science, or mathematical formulae. The justification for learning them is ostensibly that they are necessary for us to be functioning citizens, and as such they must be drilled into our brains. So we sit, day after day, as we receive these deposits of “knowledge” from the teacher. (The philosopher Paulo Freire put a name to this phenomenon: the banking model of education.)

Viewed in this light, education as we know it does seem quite like a form of social control. Even more so if we consider where our received knowledge comes from. It is almost always from some higher power, whether that be the teacher who lectures from their curriculum, the administrator who selects it, the textbook author who writes it, the test-prep lobbyist who connives to get it into our schools, or the politician who pockets the lobbyist’s bribes and puts it in. Note that there is no place for the student in this hierarchy, except at the very bottom. So long as we are the passive receptors of our own education, we are treated as if we are impressionable, inanimate clay, upon which the educational establishment can stamp whatever it pleases.

Allow me to illustrate with an example, from my very own US History class. Now, I personally enjoy history, because I find it interesting to learn about other ways of living. I also find it incredibly valuable in illuminating how society arrived at where it is today. Unfortunately, that class was rather limited on both counts.

The class was a standard college prep one, and consisted of a series of lectures punctuated with worksheets and group projects. In every lecture, our teacher would go over a bullet-pointed list of historical events, and the students would busily jot them down to memorize them before the next test. We worked like this, unit after unit, for the entire year.

As I looked around at my fellow classmates, I became rather concerned with how apathetic they seemed. Any interest in history they may have had seemed to be totally extinguished. Instead they seemed resigned to sit at their desks and swallow the historical narrative that was spoon-fed to them, without much questioning or analysis.

For instance, when we were learning about the United States’s entrace into World War I, we were given the usual story: German U-boats provoked the US by sinking the Lusitania cruiser, and sending the Zimmermann telegram to Mexico (which proposed the outlandish plan that Mexico should invade the United States), so President Woodrow Wilson declared war in order to “make the world safe for democracy.” All of the class, myself included, took this in without much consideration.

What was not mentioned (and I only found this out later, by reading histories like Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States)was that there was a significant economic motivation for entering the war as well. At the time, the United States was extremely dependent on foreign markets, with Europe being its largest trading partner. As such, its leaders were intensely concerned about keeping them open. For instance, in 1907, Wilson said that the United States government ought to protect “concessions obtained by financiers… even if the sovereignty of unwilling nations [will] be outraged in the process.” By 1915, these financiers, including the infamous J.P. Morgan, had made significant loans to the Allied powers, thereby coupling American finance to an interest in Allied victory. These economic interests, and the aforementioned historical events, coalesced and caused Wilson to declare war on the Central Powers.

This new information changed my understanding of the war drastically. World War I was not fought simply to preserve noble, democratic principles; it was also a profit-making machine. And as with every war, it served to unify the rich and poor, who were previously violently at odds, under the common banner of nationalism. That made sure the poor were sufficiently motivated to go fight and die for the interests of the rich.

None of this was covered in our class. And in general, the class lacked this kind of critical engagement with history, or any serious questioning of our venerated institutions. History was something to be memorized, not scrutinized. Yes, we learned about American imperialism in Cuba, Hawai’i, and the Phillippines, but thought nothing of that blend of greed, militarism and American exceptionalism that continues that legacy today.

I saw the effects of this “passive history” on my fellow students. It was intensely demoralizing. The usual response was to sit silently and take it all in, so they could get by with a good grade. I asked several of them how they felt about this, and one student said succinctly: “I’m just here, you know.” Another expressed the sentiment that they were simply going through the motions: get a grade, go to college, get a job and then die.

This last example is rather dramatic, but it is emblematic of a widespread attitude among students at large. They have resigned themselves to sit through excruciating tedium, to swallow received knowledge and follow orders, so they can get on to the next stage of life where they can do more of the same. This culture of obedience, stifling of independent thought, and crushing of the human spirit seems, to me, like an excellent form of social control.

But I also noticed something else – how this student apathy affected my teacher. At one point in the year, I expressed my concerns about the class, the ones that I have outlined here. To my surprise, she agreed with them. But she told me that she had very little to work with – she would love nothing more than to teach a class that was curious and excited to learn, but her students had come into the class so indifferent that it was very difficult to engage them. I can only imagine that this was rather demoralizing for her as well. But there was only so much she could do, since she had to work within the framework of the state standards.

After that conversation, I felt that I really could not blame her. Both students and teachers are trapped in this vicious cycle. From a young age, students have their curiosity beaten out of their heads, cauterized by merciless drudgery. The teachers, constrained by such factors as mandated educational standards and the whims of local politicians, can do little to change this. Meanwhile, the social order remains unquestioned, and the prevailing power structures reproduce themselves in the minds of another generation.

Now I am told that this story is not universal, since classes vary in their style, content and format. For example, AP US History lays out the entirety of American history in gory detail and leaves students to arrive at their own conclusions. But ask any student, anywhere, and they will tell you that these problems still abound, all over education.

Probably the finest example of this is mathematics education. Generations of students have been herded through the mathematics curriculum, made to memorize formulas and equations lacking any clear motivation, but which, they are assured, will be useful to them eventually. In the meantime, they are made to apply this knowledge to “word problems,” which are farcical attempts to model the real world and therefore reassure students of the curriculum’s utility. It is often a distressing and traumatizing experience, and causes students to develop a permanent distaste for math. Many of them rejoice upon being freed from such an intellectual torture.

Meanwhile, mathematicians are horrified by this state of affairs. Paul Lockhart, a professional mathematician turned schoolteacher, writes about it quite eloquently in his essay A Mathematician’s Lament. In it, he argues that the way students are taught math in school has nothing at all to do with how mathematicians view math: as art. To mathematicians, math is a joyful process of discovery that requires significant creative energy and a certain taste. Like any other art, it is a rich tradition with a remarkable history. But in schools, he writes, this has been transformed into a “confused heap of destructive disinformation.” It is a “complete prescription for permanently disabling young minds – a proven cure for curiosity.”

And if we take a step backwards, we can see the same patterns being reproduced again: the student exists as a receptacle for cut-and-dry mathematical “knowledge,” while the teacher exists to deposit these facts in their head. Students are not just taught “mathematics,” they are also taught subordination.

By now, it is clear that this situation is untenable and intolerable. We, the students of the United States, do not exist simply to be passive, subordinate automatons, or to buttress the existing social order. Education should not be a machine for indoctrination; it should be an experience of liberation, of possibility – an uplifting of the human spirit.

So, as students, what should we do?

I am inspired by a friend who told me that over the summer, they intended to read voraciously because they wanted to “take responsibility for my own education.” And they are exactly right – if we are to be liberated, we must do it ourselves.

Personally, I have tried to start small – giving books to middle schoolers on the bus in order to encourage them to read, or engaging fellow students in intellectual conversation. But that is not nearly enough. A truly emancipatory education requires us, the students, to envision new ways of teaching and learning, and to build our own systems to facilitate them. That may take the form of a study group, or workshops, or the fashioning of our own curriculum. And importantly, we ought to pay attention to those who are underserved by our current hideously broken system and go serve them ourselves.

That is not to discount the role of teachers in this new vision of education. Personally, I am immensely indebted to many brilliant, wonderful educators, who opened my mind, broadened my horizons and offered guidance that I sorely needed. But one quality that they all shared was a deep respect for the learner, and an understanding that education takes two – it is a dialogue, not a monologue. All of them were discontented with the system that they had to work within and often subverted it simply by being excellent teachers.

We ought to learn from their example. In order to bring this vision of liberatory education about, we must work from within and without, subverting old institutions while creating new ones. Only then can we reach freedom.