As with every generation that comes of age and begins to create new forms of media, the latest artistic trends are worth examining. Many note how the youth of today prefer postmodern interior design, how they write quick, streamable songs that go viral on social media, and how they tend to prefer short-form videos over the long-form media that past generations were accustomed to. But few stop to think about Generation Z’s attitude toward literature– or more specifically, poetry.

Poetry has long been the finger on the pulse of society. When Dante wrote his Divine Comedy, it was a commentary on the political and social issues facing Florence at the time as it became divided into factions and greed reigned supreme. And when T.S. Eliot wrote “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”, he knew he was ushering in a new era of modernist poetry fueled by post-World War I social trauma. But when we think of poetry today, what exactly comes to mind?

“I do recall reading something about how national interest [in poetry] spiked when Amanda Gorman read ‘The Hill We Climb’ at President Biden’s inauguration,” said one Dublin High junior, Franklin Liu, when asked about poetry in society today. But while Gorman’s poems were powerful and inspirational, they failed to inspire a poetic movement, and the temporary spike in interest for poetry soon fell. As Franklin noted, “On a personal level, I don’t know that many people who are devoted readers of poetry.”

Some argue that poetry is dying, or that poetry is already dead. In an opinion article for The New York Times, Matthew Walther writes that T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”, written more than 100 years ago, is one of the last great poems because “poetry is dead… in part because Eliot helped to kill it.”

Walther’s argument, in short, is that the movement of modernist poetry marked a transition from poetry based on the natural world to poetry based on the “fragmentation” of society into consumerism and industrial civilization. Modernist poetry, marked by jagged syntax and the absurdism of modern life, has become the end-all be-all of poetic verse.

Lately, it seems that the kind of poetry that is valued is more than just fragmented, it is excessively short. This is evident in the simple and “Instagrammable” style of Rupi Kaur. Similarly to “streamable” music and 30-second vertical video, it is not that short poems are necessarily bad, but that lately they seem too digested. Even when poems are a reflection of the times, or of one’s own diverse experiences, they are still primarily designed to go viral.

The problem with poetry of this format is that it can never truly move forward. Stuck in a format that avoids flowery language or dramatic length for the purpose of being “approachable”, there is almost no room to truly consider an idea. Issues, thoughts, and experiences are brought up and packed away with each line, and then the poem ends.

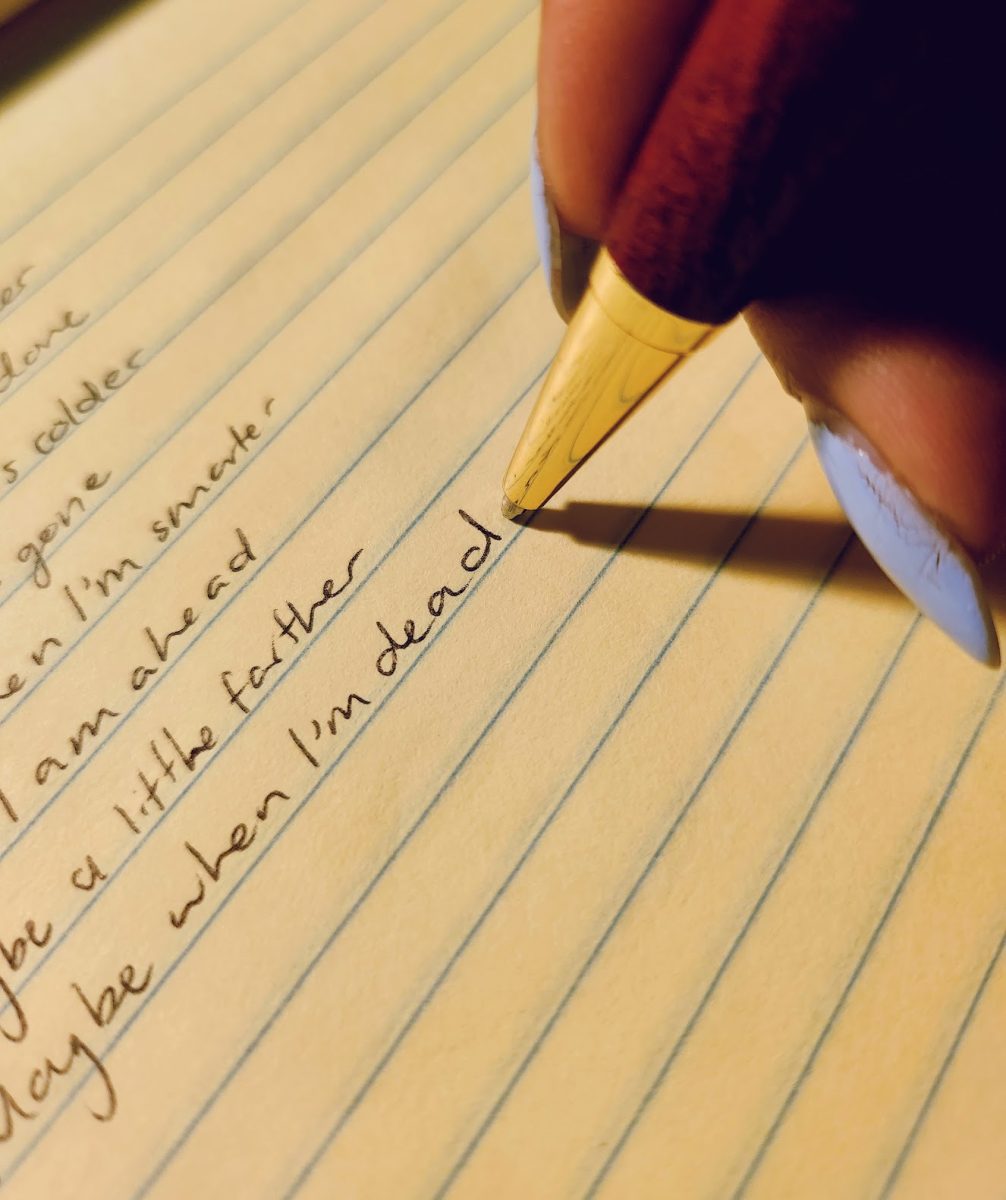

So this begs the question: Is poetry truly dead? Some, like Walther, seem to think so. But as with any art form, poetry is more than the few poets who dominate the media landscape. What had long been the privilege of the few has become the language of many, and poetry is easier to pick up and write than ever. Perhaps this means that somewhere out there are the T.S. Eliots who will usher in a new stylistic era, so that in one hundred years someone else may declare they have finished poetry off.

Franklin Liu, our Dublin High student, noted that he was quite interested in poetry. “I think I would like to try my hand more at it, as it seems like another promising avenue of self-expression.” And what did he think of the future of poetry? “No matter the circumstances, though, I am sure that poetry will endure. It is one of humanity’s oldest and finest traditions.”