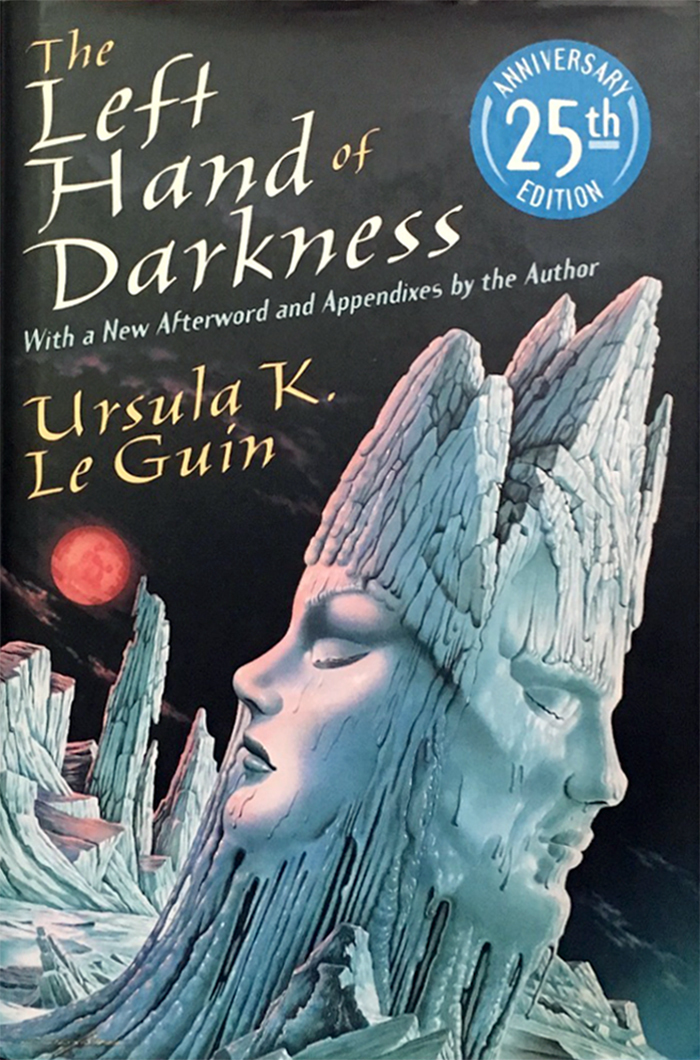

Out of all the books that I have read, few have influenced me as much as Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness. It is one of those novels that opens the brain—in 300 pages, it made me completely re-evaluate the way I see gender. The novel wasn’t just radical for me, though; it was radical for its time as well. Left Hand lays claim to many ‘firsts’: it was one of the first novels to examine gender-fluidity, and it was one of the earliest feminist science fiction books—a forebear of novels like Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Published in 1969, at the height of the women’s liberation movement, The Left Hand of Darkness rocked the science fiction world and won both the Hugo and Nebula awards for Best Novel.

Left Hand follows the journey of one Genly Ai, the Envoy to the planet Gethen. Genly, a native of Earth, is on a mission to convince Karhide, a nation on Gethen, to join the Ekumen, a “League of All Worlds.” This is no small feat: Genly is ill-adjusted for Gethen’s climate—the planet is in the midst of an Ice Age—and its people, whose physiology and behavior elude him entirely.

This is because the inhabitants of Gethen are ambisexual; they have no fixed sex but rather are androgynous most of the time, a lack of gender separation to which Genly isn’t accustomed. He struggles to reconcile this interpretation of gender with his own: at the beginning of the novel, he cannot help but see a Gethenian “first as a man, then as a woman, forcing him into those categories irrelevant to his nature and so essential to my own.” This failure to acknowledge their true nature, moreover, also causes him to misunderstand the nature of social relations on Gethen. This impedes his mission, prompting him to leave for the neighboring nation of Orgoreyn. However, his plans there ultimately go awry, and he is forced to become a fugitive. Aided by an ally, Estraven, Genly makes a brutal trek over Gethen’s glacial ice back into Karhide, and only then does he truly learn to see Gethen’s people as they truly are.

The novel is a gripping story, but it is also a fascinating exploration of how gender affects society and our perception of each other. As one character notes, on Gethen, “there is no division of humanity into strong and weak halves, protective/protected, dominant/submissive, owner/chattel, active/passive. In fact the whole tendency to dualism that pervades human thinking may found to be lessened, or changed, on Winter.” We certainly have not attained such enlightenment; our society is still stuck in these binaries.

In my own experience, I have seen how being entrenched in one half can lead to an unhealthy obsession with the other. Specifically, I am reminded of one night at a church youth retreat, when the boys’ cabin stayed up until 2 a.m. to talk about girls. One camper spoke about how he felt that he needed women to validate him, which, to use an example fresh in the public consciousness, rather reminded me of Ken’s behavior in the Barbie movie. Like Ken, he had elevated his idol to an ideal, beyond an actual person, and then convinced himself he needed this ideal for his own fulfillment.

At the same retreat, the guest pastor told us about his own emotional void, a void that had stemmed from childhood and that he had tried in vain to fill with a series of romances. He found his wholeness in God, but Left Hand presents another vision of the world, in which wholeness comes from a connection between people who see each other fully. This new interpretation of wholeness is reflected in the ending of the novel: near the end of his trek on the Ice, Genly Ai learns to see in Estraven “what I had always been afraid to see, and had pretended not to see in him: that he was a woman as well as a man” (248). His journey had been to overcome his prejudice and preconceptions, culminating in the meeting of “I and Thou.”

In her introduction to the novel, Le Guin clarifies that her novel by no means argues that we all will be, or should be, androgynous. But what The Left Hand of Darkness does do is what science fiction does best. It invites the reader to imagine another way of being, and to imagine how things might change. I found it tremendously interesting, instructive, and beautiful, and I hope you do too.

The Left Hand of Darkness can be found wherever books are sold. There are also some excerpts available here: https://www.ursulakleguin.com/left-hand-darkness

![[Book Review] Weapons of Math Destruction: The insidious danger of Big Data](https://thedublinshield.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/wmdsarticle-727x1200.jpg)