DHS students report increased struggles with mental health, post-pandemic

The past two years have been unprecedented for the world, for America and for our own community in Dublin, a truth that’s been repeated so many times now it’s almost cliché. But it is true — we were, and still are in the midst of, a global pandemic, and it has affected all of us in myriad ways.

Chief amongst these newly exacerbated problems are mental health issues, which came to the forefront of social concerns during the pandemic. Many young people and adolescents in particular have reported feeling some sort of pressure during or after isolation.

Dublin High School students are no exception, and many have stories that show the impact this global issue has had on our local communities.

QUARANTINE AND MENTAL HEALTH

I sent out an informal survey on social media that attempted to answer this very question: how has the COVID-19 pandemic affected DHS students’ mental health?

While everyone had their own individual experiences, there were certainly common threads running throughout as well. Many students answered that they had indeed struggled with mental health throughout the pandemic, and gave multiple reasons for why.

“Lacking face-to-face interaction and not having as much to do as usual made me feel tired and depressed because I’m used to being active and surrounded by others,” reported Kristen Clay, a DHS junior.

“My life became too much of a repeated, predictable pattern, which took away any sense of purpose that I felt substantially,” explained a DHS junior who wished to stay anonymous. This sentiment was echoed by many others.

Other reasons cited included oppressive home environments and struggling with distance learning. Perhaps even worse than struggling on your own is having to watch people around you struggle with their own issues, but unfortunately, that’s the reality many DHS students lived during quarantine.

“A lot of my friends who already had mental illnesses had their illnesses worsened and those who didn’t have mental illnesses might not have them now but I can see how stressed they get sometimes,” wrote DHS sophomore Danica Lee. Either way, it’s clear that for one reason or another, the pandemic and its resulting isolation proved to be difficult for many students.

Faculty member Michael Ruegg (who teaches AP Capstone and AP European History at DHS) had also observed the same effect himself. He agreed that the pandemic had indeed been difficult for most, if not the majority of people: “Anecdotally, a lot of students seemed like they were having difficulty with organization and motivation that seemed out of character.”

These students’ stories are reflective of a larger phenomenon many in the nation are now attempting to address. The CDC has an entire webpage dedicated to addressing the specific issue of increased stress and mental health troubles from the pandemic. College students have been asking their universities for ‘wellness days’ and more mental-health focused time off. Some of the groups hardest hit by this ‘psychological pandemic’ were the youngest ones — children, teenagers, and young adults.

In one report from May 2021 that synthesizes various statistics to create a more complete picture of this ongoing issue, researchers cite one statistic that found that in October 2020: “31% of parents said their child’s mental or emotional health was worse than before the pandemic” — that’s almost one-third.

“More than 25% of high school students reported worsened emotional and cognitive health” and nearly a quarter “report feeling disconnected from their classmates during the pandemic.”

Existing risk factors could increase these amounts dramatically — for instance: “Many LGBTQ adolescent respondents (ages 13-17) reported symptoms of anxiety (73%) and depression (67%) and serious thoughts of suicide (48%) during the pandemic.”

These numbers are disturbingly high, and most probably can be traced back to that prior reason of oppressive home environments, in which being isolated could be extremely damaging. Similarly, other minority groups may also have been at higher risk for mental health problems due to additional stress from experiencing discrimination in their communities.

DISTANCE AND IN PERSON LEARNING

One major center of the debate was on whether or not distance learning was effective, and if going back to in person learning was a welcome change or one that actually worsened things.

Interestingly, student responses were mixed — when posed the question whether or not distance learning was a positive change for them, almost equal proportions responded both in favor and opposed.

Many students called online learning not engaging, stressful, monotonous and increased work, in addition to citing it as a reason they struggled throughout the pandemic.

On the other hand, some other students felt the opposite — “Honestly distance learning was ideal for a lot of people including myself and being back at school makes things worse,” reported Daniel Bassilios, 11, to the Shield.

For some students, the difference was more social than academic. “It was great to come back and see real people again instead of faces on a screen, but I would be lying if I said it wasn’t nerve-wracking. I found it difficult to start conversations with new and old faces and grew a lot more anxious,” remarked Karina Fong, 11.

Mr. Ruegg was similarly mixed, finding both pros and cons in both approaches. He actually had found that “it was not easier to teach now that I’m back at school”, because, interestingly, it was “more difficult to keep attention of students which I had not anticipated”.

Indeed, while unsurprisingly none of the students mentioned this in their own responses, it does make sense. Distance learning made it all too easy to go on your phone or browse online in class, with the teacher none the wiser, not to mention all the extra time students spent online in general due to a lack of other things to do in isolation.

While undoubtedly there are many other explanations and many students’ complaints against in person learning are valid, it is possible that some students are struggling more with in person learning now because they’re not used to focusing in class for periods of time — at least compared with the truncated schedule utilized during the 2020-21 school year.

In terms of distance learning: “It was difficult to offer some of the more enriching lessons that I wanted to,” admitted Mr. Ruegg, but had favorable opinions of other features introduced during the period — one singled out in particular was the addition of office hours. “A lot of students used [it].” Office hours were shifts of open time, usually about one hour in length, every day after school where students could join their teacher on Zoom to ask any questions they had.

Some teachers have tried to continue this in-person, by offering open time after school on certain days or during lunch with the same function, though Mr. Ruegg was not able to do this himself due to lack of time.”[I] would love to do it if I had time,” he did say, suggesting that something like having office hours as part of the school schedule might be quite beneficial.

LOOKING FORWARD

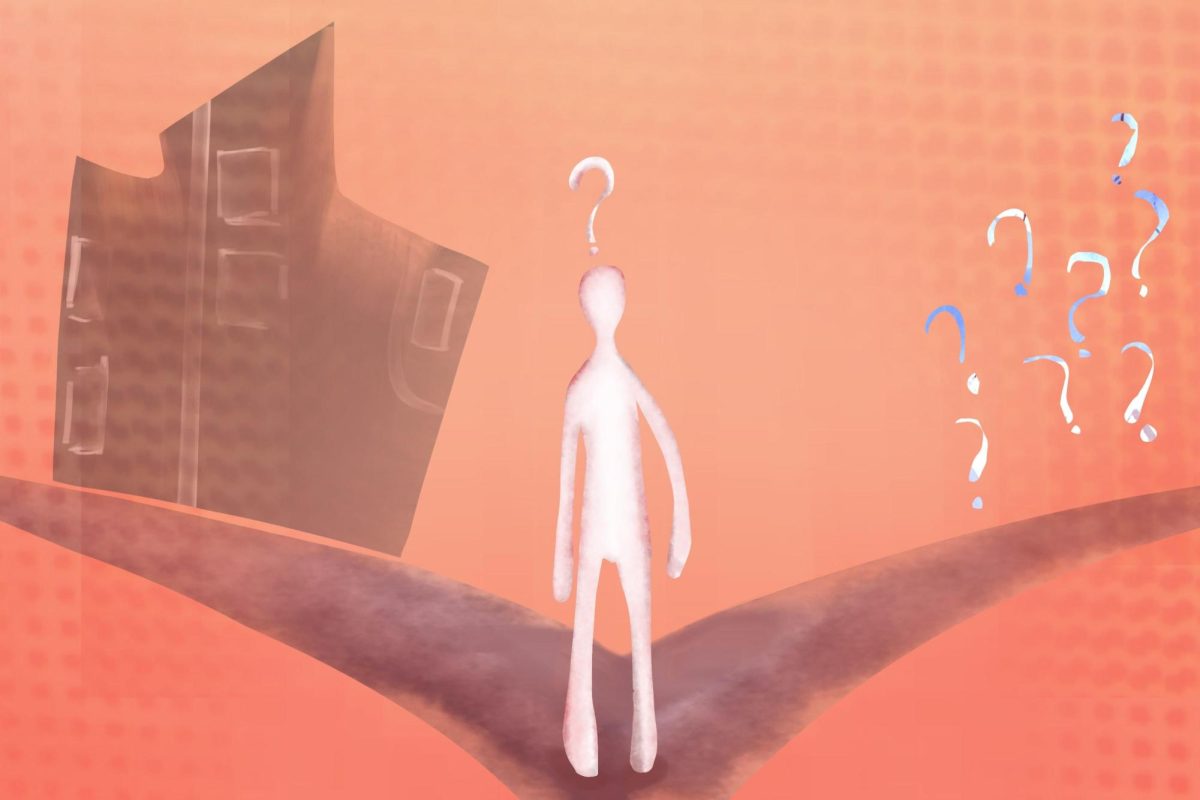

What now? It’s evident that the past two years have taken their toll on many DHS students and many students in the larger national and global community. However, it’s equally important to recognize that for each person this is for a different reason — different people respond in different ways to different things, and every student had a slightly different list of which things they struggled with and which they found positive.

There is no blanket generalization we can make about the experiences of all students, or indeed all people, in this pandemic. What can be understood is that for the average student, it is more than likely they struggled with at least one issue related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This situation can certainly be investigated further. Research on mental health of children and adolescents is still limited, meaning it’s difficult to understand the full extent of what’s going on.

And then there’s the more abstract, individual level — what will be the long-lasting effects of the coronavirus, into our college years and beyond? Certainly, there are multiple possible answers and conjectures one could make in response to this question. Many could and would focus on the devastating things it has done not just to our mental health, but to our economy, our countries, our families, and more.

When asked this question, though, Mr. Ruegg chose to take a more positive view. “Last year I saw students become problem-solvers. I saw them try everything to get back on when their Zoom crashed, I saw them bend over backwards to turn work in, I saw them become adaptable … students became very resilient. And I think that’ll stay with them for the rest of their lives.”

And that’s the crux of it. The past two years have been difficult, and to deny otherwise would be a disservice to all of us. But we — Dublin High students, Americans, humans worldwide — are survivors. We made it this far, we’ll make it all the way through. And maybe we’ll be stronger for it when it’s all over.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Dublin High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.